Deep Isolation, a company founded in 2016 and headquartered in California, launched a “Deep Borehole Demonstration Center” on February 27. It aims to show that disposal of nuclear waste in deep boreholes is a safe and practical alternative to the mined tunnels that make up most of today’s designs for nuclear waste repositories.

But while the launch named initial board members and published a high-level plan, the startup doesn’t yet have a permanent location, nor does it have the funds secured to complete its planned drilling and testing program.

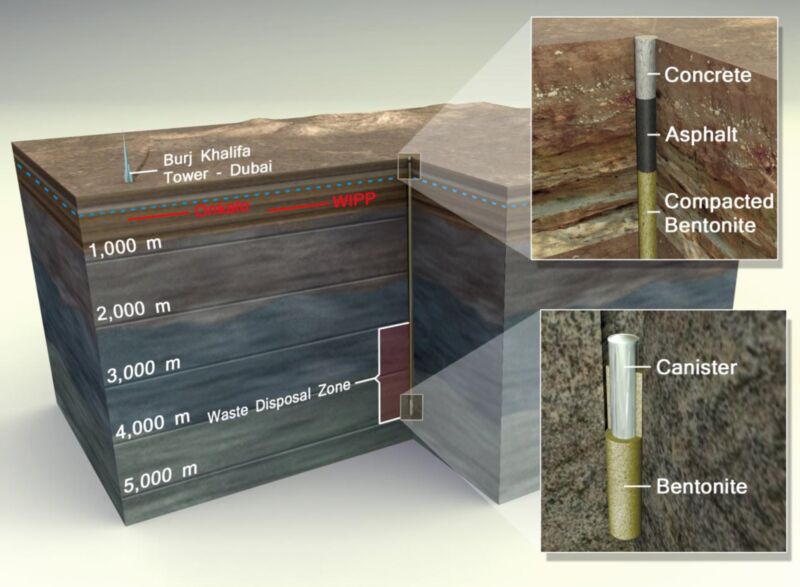

Although the idea to use deep boreholes for nuclear waste disposal isn’t new, nobody has yet demonstrated it works. The Deep Borehole Demonstration Center aims to be an end-to-end demonstration at full scale, testing everything: safe handling of waste canisters at the surface, disposal, possible retrieval, and eventual permanent sealing deep underground. It will also rehearse techniques for ensuring that eventual underground leaks will not contaminate the surface environment, even many millennia after disposal.

But it will do all that without any actual nuclear waste: “This site, to be clear, will never be used for radioactive waste disposal,” said Liz Muller, CEO of Deep Isolation and chair of the Deep Borehole Demonstration Center’s board.

“What this is intended to do is to really bring people together to understand what are the principal issues that need to be resolved before we go forward,” said Ted Garrish, the launch executive director of the center. “There's nothing really new here in terms of the actual technologies; it's just marrying them together and doing it in a nuclear environment.”

Universal canister

By the time of this announcement, the center’s first exercise at “marrying” standard oil drilling and nuclear technology had already started. In February, there was a technology demo at a borehole equipment testing site near Cameron in Texas. “We have to have an attachment mechanism for this nuclear-designed canister to attach to standard oil and gas rigging,” explained Muller.

They used a newly designed canister big enough to enclose a 14-foot-long spent fuel assembly from a Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR). They latched onto it using standard oilfield equipment, lowered it through the floor of the drill rig, and unlatched it there. They later latched back onto it and fished it out again.

With funding by the US Department of Energy’s ARPA-E program, Deep Isolation is designing a new universal canister that can fit into a borehole and take waste generated by different reactor designs, not just PWRs: “We are talking to a number of different advanced reactor companies, what is their waste form going to look like, can we design it in such a way that it will fit into this universal canister?” said Muller, who thinks they should all fit into a canister the same size as their PWR spent fuel canister used in February’s test.

Decentralized disposal

A universal canister should make deep boreholes suitable for a variety of nuclear wastes, while the depth of boreholes should make them suit a variety of locations.

At the depths that mined nuclear waste repositories are constructed—around 400 meters deep—there’s typically quite a lot of flowing groundwater that can bring contaminants to the surface. Mined repositories for nuclear waste must therefore find uncommon locations, ones where the rock is tight and the water static, ensuring that leaks at the repository won’t move far, even after millennia. But by going much deeper, Muller argues, the waste can be placed at depths where groundwater flow is typically minimal, so there’s much less restriction on suitable locations. “The geology is much more flexible than it is when you're looking at a mined repository,” said Muller. “When you're going much deeper, when you're going a kilometer, two kilometers deep, there are many more locations that are suitable.”

That means there could potentially be deep borehole disposal facilities at most of the places where nuclear waste is generated, reducing the need to ship nuclear waste to a centralized facility, such as the failed Yucca Mountain site in Nevada. “We expect the first iterations of Deep Isolation technology to be at existing waste facilities,” Muller said.

“I think if we've learned anything from the attempts to... have consolidated locations and to move [nuclear waste] across states, I think the big lesson, the big, big take home lesson is: don't do it!” said Muller. Transportation of nuclear waste is still, to this day, cited as one of the objections by the state of Nevada to the Yucca Mountain disposal site.

reader comments

152