Episode 5

David Victor

Chair of the Community Engagement Panel for the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station

San Onofre: A Lesson in Nuclear Power Plant Decommissioning

In this episode, David Victor offers insight into how stakeholders and the utility work together on the decommissioning process.

Note: This transcript is the raw transcript of this podcast. Minimal edits have been made only for clarity purposes.

Dr. David Victor (00:00):

The other challenge that’s present is a lack of a nuclear waste strategy for the country. So I think, to me, what one of the most striking things in this whole process was how many people when the plant shut down, recognized that even though the plant is shut down and they’ll remove the domes and so on, the spent fuel is going to be there forever unless we have a strategy.

Narrator (00:35):

Hello, and welcome to Nuclear Waste: The Whole Story, a series designed to explore perspectives of nuclear waste disposal. About half a million metric tons of high-level nuclear waste is temporarily stored at hundreds of sites worldwide. No country has established a permanent home for spent commercial fuel. In the U.S. Alone, one in three people live within 50 miles of a storage site. That fact may be surprising, but it’s not for lack of technical solutions. Experts worldwide agree that a deep geological repository would be the best final resting place for this hazardous substance. So what’s the delay you ask? The answers are complex and controversial. In this series, we’re interviewing experts and stakeholders representing pieces of this complicated puzzle to give you a clearer picture of Nuclear Waste: The Whole Story.

Narrator (01:33):

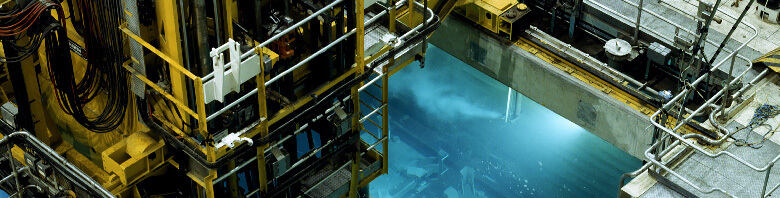

In this episode, Deep Isolation Communications Manager, Kari Hulac, interviews, Dr. David Victor, Chair of the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station Community Engagement Panel. San Onofre is a former nuclear energy plant on the coast of Southern California that’s being decommissioned.

At Deep Isolation, we believe that listening is one of the most important elements of a successful nuclear waste disposal program. A core company value is to seek and listen to different perspectives on the matter of nuclear waste, nuclear energy, and disposal solutions. The opinions expressed in this series are those of the participants and do not represent Deep Isolation’s position.

Kari Hulac (02:25):

I’m Kari Hulac, and I’m here today with Dr. David Victor, Chair of the Community Engagement Panel for the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station in Southern California. The station stopped producing electricity in 2012 and began decommissioning in 2013. The facility is home to 1600 tons of spent nuclear fuel, located just feet from the Pacific Ocean. Welcome Dr. Victor, and thank you so much for joining us.

Dr. David Victor (02:54):

Well, it’s my pleasure to be with you.

Kari Hulac (02:55):

We’ll just get started with something really basic. Can you just explain what it means to decommission a nuclear power plant?

Dr. David Victor (03:03):

Well, right in this country right now, it means taking all the fuel out of the reactor and out of the spent fuel pools, putting it into dry cask storage, leaving that on-site because we have no place for that fuel to go. That is the central political challenge for this country, around this challenge that other countries have addressed, frankly, better than we have. And then it also involves dismantling the site, which is almost as complex and expensive as building a nuclear plant. It involves figuring out which pieces you remove first, involves decontaminating a lot of stuff, figuring out how to take the most radioactive parts, reactor vessels, and so on, cut them up robotically, put them into their own dry cask storage systems and store them basically in the same way you’d store spent nuclear fuel. And then huge, huge volumes of lower-level waste that needs to go to special repositories. In the case of the San Onofre plant, most of that will go to Clive Utah, which is a facility just west of Salt Lake City.

Kari Hulac (04:06):

So what is the role of the community engagement panel exactly in this process?

Dr. David Victor (04:12):

Well, we were set up as a conduit between Edison, the operator of the site, and like most plants in this country. There are multiple partial owners, but there’s one dominant owner and operator of the site that’s Southern California Edison. And when they went into it, when they knew they were going to the decommissioning process, they also knew that they needed some better mechanism to talk to the public and understand what the public cares about, our public frankly care about because there are lots of different communities with lots of different interests. We help Edison understand what the public cares about and also help the public understand what Edison cares about and also frankly, what Edison is actually doing on the site. And that’s what we do is we’re a two-way conduit. We’re not a decision-making body. There are lots of other decision-making bodies: oversight of trust funds, oversight of safety, and oversight of all kinds of things.

Dr. David Victor (05:01):

There wasn’t a need for another oversight mechanism or a formally deciding mechanism, but there was a need for a mechanism that would make everybody more aware of each other. And I think the backdrop to that is for some parts of this community, there were contentious relations when the plant was operational and that a lot of that was brought out by Fukushima, but it had been there long before. The plant was built in an area that was more remote in California when, when it was originally planned. And then, you know, people discover they like California, so lots of people moved and now you’ve got a pretty substantial population near the plant. A lot of those members of that community are highly engaged, not all of them thrilled about nuclear power. And so, so that’s the political backdrop to this and it was an effort to kind of reset those relations with the communities. And I think for the most part has been successful in that regard.

Kari Hulac (05:50):

So, you would say that was the panel’s key objectives to kind of get that relationship, that communication going between the community and the utility.

Dr. David Victor (05:59):

Yeah. And there were ways for people to communicate before. There were, you know, all the towns and cities around the plant would have meetings of various types and councils and so on. And so, people would go to those, but they weren’t a forum that was dedicated just to San Onofre. One of the things I think was so important about the decision to set up the Community Engagement Panel and the membership of the panel is that more than half of the members are elected officials. And so they’re mayors and members of city council; they’re on school boards. And so you get, I’ve learned – I’m a professional political scientist – And I learned a lot about politics from this process, because you see all these people who are used to dealing with conflicting, local interests and managing that and we’re very good at it.

Dr. David Victor (06:50):

And they’ve just played an invaluable role on the panel and helping us understand how to, how to appreciate what different people are saying, what the concerns are, how to manage those concerns or help Edison manage those concerns better, or at least give some advice. And that’s been crucial and it’s been crucial to delivering on this two-way conduit so that people in the communities don’t just feel that Edison’s there telling them what’s about to happen, but that they’re actually able to speak up, organize themselves. And then in many cases now, have a pretty substantial impact on what happens during the decommissioning process.

Kari Hulac (07:23):

Is this a kind of unique panel? I mean, there’s many other decommissioning plants throughout the U.S. and the world. Is this unique? What have you seen happen in other communities? Maybe that hasn’t gone so well or other? How would you compare?

Dr. David Victor (07:39):

We’re not unique in the sense that there had been panels like this before. In fact, Vermont Yankee [correction: Maine Yankee] is a very important study that Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) did on best practices. That was one of the reference points for the communication panel when it was set up. And those best practices included looking at what was happening for Vermont [Maine] Yankee. It was a very important experience, where it was a panel like this. It helped guide the process; played a pretty substantial role. And they are in, in, you know, fully decommissioned with now just the spent fuel pattern is placed onsite. There was a similar panel that was set up after ours in Vermont. There are panels – there’s a nuclear plant just north of Chicago that had, that had a panel that’s similar, that was preexisting to ours. And so in that sense, we’re not unique.

Dr. David Victor (08:28):

I think what’s made us a little more unique is the size and engagement of the populations around the San Onofre site. This is a site that is between the I-5 highway, which is a major thoroughfare between San Diego and Los Angeles, highly-populated area, just north of a military base. And the plant is between the 5 and the ocean. So it’s a very small size, a long thin site. It’s kinda like the Manhattan of sites it’s a long narrow site, and then sandwiched around it is a military base. There are a lot of populations, very active communities, a huge amount of attention to the plant. Also, frankly, a number of fairly unique technical challenges and particularly the seismic risks. And so, that’s what makes the whole situation a little more hyper-charged and a little more unique compared to other plants. I think Diablo Canyon, north of here, which is another California site, that’ll be decommissioned in a few years, will have something similar – but the difference between Diablo Canyon and the San Onofre plant is that Diablo Canyon is out in a much more remote area, has a different ownership structure in terms of the land around there on a much, much larger site.

Dr. David Victor (09:42):

So, so this is really, it’s a very special case. And I think people need to look at our experience with that in mind and not everything from what we’ve done is going to be applicable to other places. But a lot of it is.

Kari Hulac (09:53):

So, would you say that those are some of your challenges and obstacles in dealing with such a complicated landscape with the population and all the different facilities around there and the base? Are there other obstacles you’d like to mention or challenges that you’ve, that you’ve tried to overcome?

Dr. David Victor (10:11):

I will say that there are really two looming challenges that make all of this hard and maybe particularly hard at a site like this. The San Onofre site where there’s so much attention to it. One of them is the issue of trust. You know, when you look across trust in all institutions has been going down, it’s related to a lot of things: polarization politics, and different sources of information, you know, on and on. And that’s a dissertation in itself, many dissertations in themselves about why people don’t trust institutions, the way they used to. But that’s particularly true of government and particularly true of big companies. And so, if people are looking at the plant and skeptical of what’s going on and are also not trusting in institutions, then everything seems suspicious. So that’s one challenge that is just omnipresent. The other challenge that’s omnipresent is a lack of a nuclear waste strategy for the country.

Dr. David Victor (11:04):

And so I think, to me, one of the most striking things in this whole process was how many people when the plant shut down, recognized that even though the plant is shut down and they’ll remove the domes and so on, the spent fuel is going to be there forever unless we have a strategy. So, we’ve spent the bulk of our time actually on that strategy. What do we need to do in Washington? I’ve gone to testify a lot of time, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, other people building political support, spent a lot of political support for this, but we don’t have enough to carry us over the finish line – that was before the pandemic has now changed political priorities and focus. And so that’s that other, this lack of a, of a waste strategy, high-level nuclear waste strategy, is a really serious problem because it means that all the debates about what to do at this site and at SONGS in particular, in the spent fuel pad, those debates are much more intense because not everybody can reliably see some end of this process.

Dr. David Victor (12:02):

I think one of the things that is interesting is that there’s a, almost a cultural disconnect. So in the engineering world, you build something like a spent fuel storage system, made out of stainless steel, do the best job possible. The system at San Onofre is especially hardened against seismic risk, it’s underground, or it’s in a highly reinforced concrete bunker basically. And the evidence in the industry so far with canister systems that are now more than 40 years old, is that there’s no significant risk of canisters failing of this kind of corrosion, but you need to monitor them. And so from a, when an engineer looks at that, they’re comfortable with that idea cause he has to have a monitoring system, we have multiple layers of monitoring, you have an idea of what you’re going to do. If you find a crack, although nobody’s found the spent fuel systems cracks, I found cracks in that stainless steel and other kinds of applications, which are much more prone to cracking, but that’s all kind of comfortable in the technical world.

Dr. David Victor (13:00):

And then for people who are not in that technical community or don’t trust what’s going on, all that seems scary. And it all seems like it relies on inventing technologies in the future and what happens if we don’t invent them and so on. So that’s the, you know, once again, we come back to this problem of this kind of disconnect in how people are seeing things at the plant because of their level of comfort with the institutions that are overseeing this. And because they see that we’re going to have to be dealing with this potentially for a very long period of time. To me, the most important interim storage questions right now have to do with these sites happens that right now. There are three sites.

Dr. David Victor (13:37):

There are three that have moved forward. 1. A long time ago in Utah that for political reasons has cratered. It seems the PFS. Two that are now emerging, actually very close to each other, but there’s the border between Texas and New Mexico between them. So one’s in New Mexico and one’s in Texas and that’s probably a pretty good thing since we’ve got some diversity and political systems there and see, see what happens. So those are moving forward. And I think those are going to be very, very important because if you’re at a site like San Onofre, there really is no reason to have spent fuel across dozens and dozens of different sites. When the reactors are operational, it doesn’t really matter very much cause you have to have some fuel onsite and for operational reactors, but when the reactors are closed, that’s not something we ought to be at least moving that to an interim storage facility.

Dr. David Victor (14:22):

I think that’s the right way to go. And I think at the same time, we need to take a completely fresh look at what the long-term strategy is going to be. Yucca, I think the ship may have sailed on the Yucca. You’ve got now in the current electoral cycle, you have the presidents on the Republican side, Anti-Yucca, you have the Democrats, most of them for the most part, Anti-Yucca and the Republicans in favor of Yucca. Now they’re kind of everyone agrees that Yucca’s a problem and not everyone, but a lot of people. And that’s, I don’t, I don’t, in that world, I don’t know if, how, I don’t know if it matters what the actual technical characteristics are of the Yucca site. Politically, it’s a poisoned prospect. And so that’s why deep borehole is so interesting. That’s why following the kind of Finland model or the Canada model and other countries, even what we do in siting of hazardous sites elsewhere in the United States of getting different communities to in effect bid for the opportunity to host a site like that, we ought to be more creative about it, and it’s not rocket science.

Dr. David Victor (15:26):

We’ve done this lots of other areas. We just have done a horrible job on the nuclear side.

Kari Hulac (15:31):

Your local Congressman assembled a task force to address federal policy and technical challenges around SONGS (San Onofre Nuclear Generation Station). I know they just released a report recently making 30 policy recommendations. Are there any highlights of this report that you’d like to call out? And what kind of role will the report play in your work with the SONGS panel?

Dr. David Victor (15:52):

I think the good parts of the task force report are the attention to the need for a long-term strategy here and the need for a good monitoring and assessment program at the SPC and so on, which is what is going on already. So that’s great, but the political solutions to this – interim storage, long-term storage – as political solutions are not there yet. I thought it was a little mystifying that there wasn’t more attention to interim storage. And I think that may reflect the politics. It may also reflect is to co-chairs who seem skeptical of everything related to nuclear power and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. I’m not sure that’s actually helpful because skepticism is a great thing in life, but you also have to get things done. And so you ought to have some vision of where and how you can work with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and other players.

Dr. David Victor (16:42):

So, I think it was kind of a mixed bag and involved a huge number of people for a long period of time. I think it may be hard for that report to get a huge amount of traction because we’re in a different political environment right now with the pandemic and stimulus and so on. I guess I’d say that there some parts of the report that are really disturbing and they’re actually the parts of the report that did not get as much consensus as the first chapter, the opening chapter, which was on the political strategy, and those parts of the report have to do with the technical issues around monitoring and cracking of canisters and things like that. Where I think the record, frankly, drifted away from the reality of the science. And that’s unfortunate, always, to see that the report wasn’t peer-reviewed. It, when you hear taskforce, you think it’s going to be a consensus task force, but in reality, when you look carefully, a substantial number of people didn’t agree with some, at least some significant parts of the report. Having been on many consensus task forces in my life and having chaired a few, I found that part pretty unusual cause we would never, as, as a rule, you’d never carry a task force, that’s supposed to be a consensus activity, to a conclusion without actually having a consensus or understanding why you don’t. So that part of it, I think was unfortunate. But I think overall I’m delighted to see more attention to this, to this topic and in particular to the political changes that we need.

Kari Hulac (18:10):

Well, let’s see. To close out today, is there a question I didn’t ask that you think is really important to kind of the general public type of listener to understand? Any closing thoughts you’d like to leave us with today?

Dr. David Victor (18:21):

Yeah. I think there’s a couple of things that are very interesting. We have a tendency to focus on the most visible and politically-charged aspects of nuclear power plants and their decommissioning process. And thus today we’ve talked about, you know, spent fuel and interim storage and so on very, very important topics. I think it’s also really important to recognize that these plants are a critical part of a community. They’re major employers and they’re major tax suppliers to the tax base and when a plant shuts that changes quickly. And then when a plant gets through the decommissioning process, that changes yet again in a much more extreme way. And I am concerned that we have over-weighted the highly emotive aspects of decommissioning and underweighted these economic and local relationship questions, frankly, with the local, with the local communities. And one of the reasons that the community engagement panel was set up the way it is with, with elected officials, with people from lots of different walks of life sitting on the panel, was so that we can make sure, including organized labor, so that we could make sure that those different perspectives are reflected.

Dr. David Victor (19:32):

And you see that in terms of the economic impact of these plants when they decommission. You also see in terms of relationship with the first responders communities, because the people often don’t recognize that while there may be onsite first responses: security, fire, medical, and so on, the defense in depth comes from a plant being able also to rely on a larger community and first responders in the larger community. And, and they’re a big part of building up those capabilities, and then when a plant shuts that can change very quickly. A big chunk of what we’ve dealt with on our panel has been around that. Bringing attention to that topic and then helping the first responders and Edison come to reasonable agreements. So that there’s a better glide path from the operational plant to the non-operational.

Kari Hulac (20:20):

And how long are we talking? I mean, you’ve already been doing this for quite a few years. What, what, is there an end in sight? Like 10 more years, or when is that unknown right now?

Dr. David Victor (20:30):

Helping manage a really important process of decommissioning has a big impact on the communities and doing it in a way that’s fact-based and has a much higher flow of information than we’ve seen in any of the other plants that have gone through something, something similar. I think that’s first and foremost really important for the local communities. But, it’s also important, hopefully, cause we might be establishing some models or best practices or contributing to models and best practices that can be followed in other places, especially where plants are, or New York communities that are highly focused and engaged on that. That was more than six years ago. And this summer, the Edison folks will finish the last of the offloading of this, of the fuel from the spent fuel pools. That’ll be a big, that’ll be a big moment because then it’ll shift basically from the offloading campaign to a full bore D and D campaign. That’ll run roughly a decade after that.

Dr. David Victor (21:33):

And there will be some [Taylon] activities. At some point, this site will go back to the Navy. They own the land, they’re already started taking back the site on the other side of the I-5 highway. I will say one thing about the schedule, which I think has been very interesting and we learned this among other places by visiting the plant North of, North of Chicago, is now that you have private contractors that are specialists in decommissioning, there’s been a lot of learning. And so they’re doing it faster. They’re doing it plausibly safer. They’re doing it at a lower cost than would have been the case. If you had a bunch of individual electric utilities that are specialized specialists in running electric plants, decommissioning their own plants. And so I think that’s a big deal. I think that I hope that we will see some big benefits from that kind of specialization for the San Onofre site because they’ve contracted with one of those specialist companies and I would not be at all surprised to see that it’s got to run faster.

Kari Hulac (22:33):

Great, great. Well, thank you so much for joining me today. I learned a lot and I wish you the best in your work there. And I hope to get down there and visit it in person.

Dr. David Victor (22:43):

Well, please, please come visit. It’ll be a, right now all of our meetings, by the way, are by Skype and all of our meetings, even when they were in person are all up on the website and we’ve invested, a whole lot of people have invested a whole lot of time in making SONGScommunity.com, a highly informative site, a lot of information about the decommissioning process. And so please do come visit.

Kari Hulac (23:06):

Great. Thank you so much. Have a great day.

Narrator (23:10):

Thank you for listening. We hope you’ll share this podcast with others and feel free to send any comments or suggestions to podcast@deepisolation.com. You can visit deepisolation.com to learn more. At Deep Isolation, we believe that listening is one of the most important elements of a successful nuclear waste disposal program. A core company value is to seek and listen to different perspectives on the matter of nuclear waste, nuclear energy, and disposal solutions. The opinions expressed in this series are those of the participants and do not represent Deep Isolation’s position.

Nuclear Waste 101

Understand more about nuclear waste and its implications for you and your community.

FAQS

Deep Isolation answers frequently asked questions about our technology, our process, and safety.