Episode 8

John Lindberg

Public Affairs Manager, World Nuclear Association

How Public Perception Can Impact Nuclear Energy

In this episode, John Lindberg, Public Affairs Manager at the World Nuclear Association, speaks about the impacts of radiophobia and the public's perception of nuclear on the nuclear industry.

Note: This transcript is the raw transcript of this podcast. Minimal edits have been made only for clarity purposes.

John Lindberg (0:10):

We need to make sure that in the climate change conversation that nuclear isn’t just in a peripheral role, but rather, how do we place nuclear energy center stage given the everything that nuclear can do in terms of fighting climate change?

Narrator (0:26):

Did you know that there are half a million metric tons of nuclear waste temporarily stored at hundreds of sites worldwide? In the U.S. alone, one in three people live within 50 miles of a storage site. No country has yet successfully disposed of commercial spent nuclear fuel, but it’s not for lack of a solution. So what’s the delay? The answers are complex and controversial. In this series, we explore the nuclear waste issue with people representing various pieces of this complicated puzzle. We hope this podcast will give you a clearer picture of Nuclear Waste: The Whole Story. We believe that listening is an important element of a successful nuclear waste disposal program. A core company value is to seek and listen to different perspectives.

Opinions expressed by the interviewers and their subjects are not necessarily representative of the company. If there’s a topic discussed in the podcast that is unfamiliar to you, or you’d like to more closely review what was said, please see the show notes at deepisolation.com/podcasts.

Kari Hulac (1:46):

Today, we’re talking to John Linberg, Public Affairs Manager at the World Nuclear Association. John is a radiation and nuclear power communications expert who focuses on the impacts of radiophobia and the public’s perception of nuclear energy, which is also the subject of his doctoral studies at King’s College London and Imperial College. Thank you for joining us today, John.

John Lindberg (2:11):

Ah, pleasure is all mine. Greetings from a very wet and gloomy London.

Kari Hulac (2:16):

Great, well stay warm and dry there. First off, I know you’re interested in how pop culture shapes the public’s opinion of anything with the word “nuclear” in it and how their fear has helped coin the term “radiophobia”. Please define that term and share a bit about its history.

John Lindberg (2:35):

Radiophobia is essentially the very clear disconnect that exists between what people perceive radiation to be and what radiation science tells us that it actually is. So most people would think that radiation is something that is uniquely dangerous, something that poses a threat, not only to ourselves but also threats to future generations. Whereas science tells us that of the many sorts of environmental threats that we face, radiation really isn’t something to get too concerned about. And radiophobia is really that, it isn’t a phobia in the clinical sense. And pop culture has to say, has played a major role in this. You know, all of us, most of us, have watched the Simpsons where we’re all thinking about Homer Simpson sitting and eating nuclear waste out of a, of a big barrel with a warning sign on it, or, or indeed HBO’s Chernobyl service that came out not that long ago.

John Lindberg (3:36):

And pop culture essentially helps us to put images to something that we cannot see because after all radiation is invisible to all our senses. We can’t smell it, we can’t hear it, we can’t taste it. So the only way for us to really make sense of radiation is to use images that’s given to us by pop culture or be it something that we were reading or even the history. And when it comes to radiation, if you look at the history of radiation, we started off thinking that it is the coolest thing on the planet. We would use radiation for everything, anything from painting your watches to, if you wanted to get it started nicer skin complexion, you could use slightly radioactive skin creams. It’s only then really after the second world war, that radiation starts to become something quite different, something more ominous we started connected with cancer.

John Lindberg (4:34):

And then obviously, the bomb and the bomb starts to play a really, really big role in the way that we start to make sense of radiation. And really at that point, making the connection from the nuclear bomb to a nuclear reactor and they both are radioactive, all the sudden we start to see these sort of bridges being built, “Oh, God, radiation is everywhere.” Which means a nuclear reactor is probably something quite close to a nuclear bomb, and that’s really why the history of radiation and the way that radiophobia impacts our lives today is so important to understand. And indeed, how pop culture played a major role in that.

Kari Hulac (5:17):

Have you seen people’s perceptions changing at all? I can completely understand the fears of the past. You know, and, and, and you deal with people worldwide. You’re educating people worldwide. Do you see differences in attitudes by countries, say, you know, where you are in the United Kingdom or Japan, US?

John Lindberg (5:37):

Yeah. I mean, you can definitely see that there is a difference in attitudes. But let’s just say on a, on a country basis, I come back to that in a second. It’s also a lot to do with when were you born? So for instance, my generation, so I’m going after the end of the cold war, my generation, we never grew up with this sort of visceral fear of nuclear war. For me, nuclear war is an abstract concept that doesn’t really mean anything on an emotional level, whereas my parents and my grandparents, for them nuclear war and the impact of the war, was very, very real. Conversely, the history and memory of Chernobyl is nothing that I remember. But my grandma still remembers to this day, how she feared the clouds and because the clouds are carrying radiation from Chernobyl.

John Lindberg (6:34):

So whenever we talk nuclear at home, she automatically starts thinking about these clouds. And on a country-to-country basis. You also see a major difference. So here in the UK, people have a much more relaxed relationship with nuclear power. It hasn’t really been any major incidents or, or anything that’s really given rise to that level of fear. In America, you would find that a lot was connected to the nuclear bomb and to fall out from the weapons. And Chernobyl didn’t really play a role in America, full stop. Whereas in Japan, you have this sort of unique perception challenge where you have the nuclear bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the sort of cultural trauma that that brought. But also you have the accidents at Fukushima Daiichi not even 10 years ago. So in Japan, you find that this sort of radiophobia is, is much more present in people’s minds. And it doesn’t take much for that to manifest, be that in increasing anxiety, social stigma, or any of the other well-known side effects of radiophobia.

Kari Hulac (7:51):

So tell me a little bit about your organization. The World Nuclear Association is an international organization that promotes nuclear power and supports companies that are part of that industry. So what are your most pressing goals and challenges in your role there at the moment?

John Lindberg (8:07):

So, as you say, the World Nuclear Association represents all parts of the nuclear industry from uranium mining to reactor vendors, operators, to waste management companies. So for us, we really spread the important message of why nuclear energy matters. And there’s a couple of really big challenges that we’re facing, I suppose, as an industry, and by extension, WNA faces some as well. Climate change is clearly one of them. We need to make sure that in the climate change conversation that nuclear isn’t just in a peripheral, but rather how do we place nuclear energy center stage given the everything that nuclear can do in terms of fighting climate change? We have the challenges and the opportunities presented by the UN sustainable development goals. Clearly clean, affordable, and reliable energy is crucial to everything that we do.

John Lindberg (9:12):

Doesn’t matter if we’re talking about food production, education, women’s empowerment, you name it, energy will be there, and energy will be crucial. And it is a tragic matter of fact, that we still see just under 1 billion people around the world, not having access to electricity, let alone any sort of clean electricity and nuclear can play a crucial role, both building large reactors, and, and small reactors. So we are engaging with national governments and international bodies, UN, the International Energy Agency, so on and so forth. Making sure that nuclear is represented at all levels of conversation. And thirdly, I suppose more pertinent today, is the issue around nuclear waste and the European Union’s whole work around the taxonomy where nuclear, as things currently stand, would be excluded from sustainable financing initiatives because of this perception of nuclear isn’t sustainable, whereas far less sustainable energy sources such as natural gas is included. So we are spending a lot of time engaging with stakeholders around the world, highlighting just how sustainable nuclear is and just how important nuclear is to building a truly sustainable future.

Kari Hulac (10:40):

So the key thing about moving forward with nuclear energy is that there’s the problem of the waste that hasn’t been permanently disposed of. What do you see the conversation around nuclear waste changing, given the value of nuclear energy as a carbon-neutral energy source? How does that play into your work? And do you hear that raised as an objection to supporting nuclear energy?

John Lindberg (11:05):

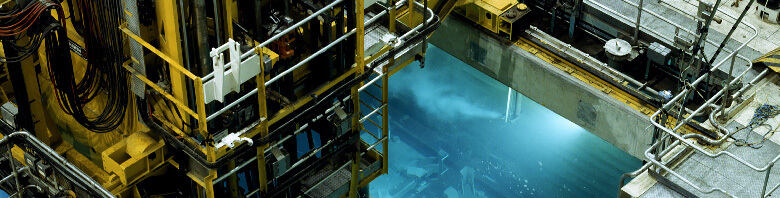

I mean, absolutely. Nuclear waste surfaces in more or less any conversation that we are having around nuclear’s role in, in fighting climate change. The challenge here is really that it is a perception issue as much as anything else. It is perceived that we haven’t resolved the question or the problem of nuclear waste, but the thing is, ever since the civil nuclear industry emerged, we have been looking after the waste in a very responsible fashion. Civil waste has never harmed anyone and we know how to handle it. Yes, there is the question of final disposal. But it’s also, if we’re comparing nuclear with other energy sources, nuclear waste is very small in quantity. And in terms of handling it, it’s, it’s relatively simple, especially if you compare to a gas, gas, or coal-fired power plant, it’s pretty hard to, to, to handle the CO2 or the ash that comes out of the, of the, of the chimneys. Whereas nuclear waste is ceramic or metallic. In some cases, it’s easy enough, you stick it into a pond and then you have it on-site, but yes.

Kari Hulac (12:26):

Right. I bet most people may not even realize it’s just a little pellets, correct.

John Lindberg (12:29):

Oh yeah, totally. I mean, I feel that they’re about that size and you, and you get an absolutely incredible amount of energy out of it. And that’s the key because there’s so much energy and so little raw material, the amount of waste that comes out it’s teeny tiny. Yes, we, we need to make more progress on, on establishing if you like repositories or recycling, because at the end of the day, what comes out of the reactor, most of that is still uranium. And we can, there’s plenty of energy in that. There’s plutonium, which we can use for electricity generation and the other elements as well. So it’s getting policymakers, I think, to, to, to realize that we resolved the question that the technical questions around nuclear waste management decades ago, it’s really a political one. They need to decide. Do you want to recycle some of it? Do you want to recycle all of it, or do you want to just use it once and dispose of it in repositories or cohorts? So it’s a political question, not a technical one.

Kari Hulac (13:38):

Now you’re studying for a doctorate in philosophy focused on risk, communication, and radiation, and you’re completing a master’s degree in medical radiation sciences. So in your spare time, you seem like you’re probably pretty busy there, but tell me, what are you learning in the course of your studies? Are there some facts you can share to help the public understand the risks of radiation associated with nuclear waste?

John Lindberg (14:01):

Yeah, so, I think the one thing that becomes abundantly clear when you start to, to, to really study and research questions around radiation is that we as a community, be it with the radiation community or the community, we learned to talk about radiation risks in isolation from other risks. We don’t put it into context and we don’t put it into perspective, and that’s a huge problem. You know, we don’t talk about any other risks that way. So why would we do that by radiation? You know, nothing in life is without risk. And I, I don’t cycle in London because the risk of being run over by a bus is pretty high. It was perceived as high. Whereas living in London in itself is probably even worse because of air pollution.

John Lindberg (14:49):

And that’s something that, especially in my Ph.D., has spent a lot of time looking into the way that we, we make sense of the world if you like. Cause at the end of the day, we are all emotional bias creatures. Most of the way that we make sense of the world is really gut feeling and there’s nothing wrong with that. But what’s important is to understand that because we often, especially in the nuclear community, we make this sort of flawed argument that we’re all rational. So, and given that we’re all rational, we just need to give people facts about nuclear power or radiation, or nuclear waste. So it comes down to that, you know, we need to change the way that we talk about ourselves, and in doing so, we need to, if you like become more human. I think that’s really what, what I’ve found, which is so important to get out to people in, in, in the nuclear community.

Kari Hulac (15:44):

You know you make me think about just the generational thing again, in terms of how people will change. You know, I see a lot of millennials really passionate about nuclear energy in the context of climate change. And maybe, do you think there’s a possibility that just the growing understanding of climate change will kind of lead to more acceptance of the fact that nuclear energy could be a solution, could be part of the solution to that, and maybe coming to terms with, yes, there is radioactive waste, but we can deal with it safely and responsibly with a really low risk, then maybe nuclear energy can be part of the mix.

John Lindberg (16:25):

Yeah. I mean, that’s a brilliant question. And in many ways that strikes right to the heart of many of the conversations that we’re having. Nuclear power and climate change is a tricky conversation to have. Some evidence points towards what’s called reluctant acceptance, that people understand that we might need nuclear for a while, but then as soon as we find something better, we can ditch nuclear for whatever that solution is. So it’s a double-edged sword. So on the one hand I think that the bigger challenge really is to get people to get comfortable with nuclear. And we can do that in a number of different ways. Climate change is really scary. You know, I remember when I started to really understand climate change, it scared the living daylights out of me. And for a long time, I was just too afraid to engage with it.

John Lindberg (17:20):

I disconnected and a lot of people have done that. So talking about nuclear in the climate change context is it can be helpful, but I think we’ve really need to be having a much broader conversation about what makes nuclear power such a valuable power source, be that fighting poverty, be that addressing energy poverty, be it creating artificial fuels, be it powering a more equitable society. I think that that’s really where we can build coalitions for nuclear, but it’s going to be positive. Cause I think that’s what we need to do. We need to build a positive momentum around nuclear. That will then start to get into the conversations around climate change because if we put all of our bets into the climate change basket, we’ll struggle because if we look at how the energy arena is being perceived, solar and wind are having very, very high favorability ratings.

John Lindberg (18:28):

People think about these energy sources and they get feelings of hope that this is something that’s going to bring, literally in the case of solar, a brighter future. The problem is obviously that we can’t do it with just solar and wind, there just isn’t a way, and the only way to do it in a low carbon way is with nuclear. And that’s why I think we need to bring the conversation around nuclear to, in a much broader arena again, and talk about all the things that nuclear can do rather than focusing on that tiny, tiny sliver that’s climate change. And that, and that’s a challenge. And I don’t think the industry has gotten that balance right, just yet, but we will live and we learn right.

Kari Hulac (19:17):

What does the World Nuclear Association do in terms of educating people about the waste? Like, do you have, I mean, do you have favorite solutions that you support? I mean, I know in, you know, closer to where you are, Finland and Sweden have had some success moving forward with their permanent disposal solutions. You know, what, what have you learned about those countries or other alternative sources of disposal?

John Lindberg (19:45):

So the World Nuclear Association is completely agnostic when it comes to waste management solutions. We recognize that certain countries have certain historical or legislative histories that make certain solutions seem more favorable than others. Some countries will want to recycle some of it. We see that for instance, in France and in Russia, but Germany has also been recycling parts of its waste. Some countries want to recycle all of it. Again, Russia is very much leading the way and a lot of that sort of R&D work, but in the United States, you see a lot of very exciting startups looking at reactor concepts that essentially can recycle theoretically up until about 97% of all the waste. Equally some countries like the ones you mentioned, Sweden, Finland, they have gone down for a different philosophy, which is that you use the fuel in the reactor, and you do that once, and then you send it off to, to a final repository.

John Lindberg (20:50):

And it’s really up to governments to decide what suits them the best. And again building repositories has for a long time been seen as the only solution. And I would obviously take, take issue with that. For instance, some countries might find it that it is too expensive to build a repository, especially for smaller countries. They might only have one, two reactors. Building a full site, a proper repository might just be too expensive. So some companies look then upon steps like international repositories, where you send waste from different countries into a central repository. And then we have other solutions like deep boreholes solutions. And really as far as we’re concerned, you know, off you go in terms of, find as many exciting solutions as possible, we are happy to write about them. We got some really, really, really good information papers cause you spoke earlier about education.

John Lindberg (21:55):

And, and for me, I think it’s really exciting that Finland has made such good headway on its repository. And when Onkalo opens up for the first waste or spent fuel to be shipped off and placed in the repository, I think at that point, we will be able to say to anyone that challenges the nuclear industry, by saying, well, look guys, you don’t have a solution to waste because well, yes we do, we have the repository of which is open and we have all of these other exciting solutions that we are currently developing. And I think that’s really going to be a game-changer. And it’s going to make it easier for the nuclear industry, I think to bring its case as well. On the climate change arena, given the waste keeps cropping up time and time again.

Kari Hulac (22:45):

Thank you so much John I’ve learned a lot talking with you today and I look forward to learning more from your organization.

John Lindberg (22:55)

Thank you so much.

Nuclear Waste 101

Understand more about nuclear waste and its implications for you and your community.

FAQS

Deep Isolation answers frequently asked questions about our technology, our process, and safety.