Episode 14

Talia Martin

Tribal/DOE Program Director of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes Tribal Department of Energy

How Shoshone-Bannock Tribe in Idaho Navigates Nuclear Waste Issues

In this episode, Talia Martin explains the role she holds as a Tribal/DOE Program Director and the past and current relationship between the Shoshone-Bannock Tribe and the U.S Department of Energy from a nuclear waste lens.

Note: This transcript is the raw transcript of this podcast. Minimal edits have been made only for clarity purposes.

Talia Martin (0:10):

What’s another interesting part of this is that private federal partnership where you had advanced reactors and a cooperative agreement between DOE and that private company. So where do the tribes fit in has always been a question that is not entirely been answered by DOE nor by the company.

Narrator (0:37):

Did you know that there are half a million metric tons of nuclear waste temporarily stored at hundreds of sites worldwide? In the U.S. alone, one in three people live within 50 miles of a storage site. No country has yet successfully disposed of commercial spent nuclear fuel, but it’s not for lack of a solution. So what’s the delay? The answers are complex and controversial. In this series, we explore the nuclear waste issue with people representing various pieces of this complicated puzzle. We hope this podcast will give you a clearer picture of Nuclear Waste: The Whole Story.

We believe that listening is an important element of a successful nuclear waste disposal program. A core company value is to seek and listen to different perspectives. Opinions expressed by the interviewers and their subjects are not necessarily representative of the company. If there’s a topic discussed in the podcast that is unfamiliar to you, or you’d like to more closely review what was said, please see the show notes at deepisolation.com/podcasts.

Kari Hulac (01:58):

Hello, I’m Kari Hulac, Deep Isolation’s Communications Manager. Today I’m talking with Talia Martin, Director of the Tribal Department of Energy for the Shoshone Bannock tribes located on the Fort Hall reservation in Fort Hall, Idaho near the Idaho National Laboratory. The Tribal Department of Energy’s mission is to monitor DOE activities to ensure they are protective of the tribe’s natural, cultural, and human health. The Tribal Department of Energy promotes the responsible management of tribal energy resources in a manner that is self-sustainable, economically feasible, as well as biologically and culturally sensitive for the Shoshone Bannock tribes. Welcome, Talia. Thank you so much for joining us today.

Talia Martin (02:44):

Thank you. It’s good to be here. And when I say here, I mean, virtually since I’m still in Fort Hall.

Kari Hulac (02:50):

That’s all right, are you up in Fort Hall right now?

Talia Martin (02:53):

Yes, I’m actually at our Tribal DOE offices amongst the tribal business buildings.

Kari Hulac (03:00):

Great. Great. All right, well, let’s just get started here. Just first of all tell me about yourself and how you became interested in nuclear issues through the work that you do with the tribe.

Talia Martin (03:12):

Sure. Well, currently I’m the Tribal DOE Director for the Shoshone-Bannock tribes and we operate as more of a liaison between the tribes and the Department of Energy, which is the office of Idaho operations is who we mainly work with. But before that, and so I’ve been here six years, but before that, I was as an environmental scientist. I’ve worked with tribes for about 10 to 11 years, and I worked for the Environmental Waste Management program for the tribes, which dealt with different types of environmental issues completely different than what I do here now, working with the DOE and nuclear energy issues.

Kari Hulac (03:53):

Before we get more into the nuclear issues, I would love to hear some of the history of the reservation and the culture of the tribes to help our listeners better understand the community at large and feel free to describe challenges that their tribes have faced.

Talia Martin (04:08):

Sure. So you mentioned that we’re from Fort Hall, Idaho. So this is the Fort Hall Indian reservation. We’re in Southeastern Idaho. It’s somewhat of a desert compared to Northern Idaho where people like to just speak about. Nonetheless, we have about 6,000 tribal members here, a pretty thriving economy in this area with gaming, agriculture and we were established initially by the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868. And we adopted, the tribe adopted a constitution about 1934. So our governmental structure and all of that are different. Something that if you’re working with different tribes that’s probably one of the key things you should understand is the governmental structure for us. The governing body is the Fort Hall Business Council and is comprised of seven members. Well, six members and one chairman. We have elections every two years, the terms by every two years.

Talia Martin (05:09):

So that’s the leadership AKA my bosses. But you know, they’re elected representatives of the people, and as a tribal member as well, I need to be involved in that, those elections. So we own about 98%, the tribes owned by 98% of the tribal land. We also have contaminated environmental health issues that we deal with.

So as far as the challenges with environmental issues that the Fort Hall reservation deals with, one of them being the Eastern Michaud Flats superfund site. That has to deal with phosphorus processing from some of the private industry. Additionally, we have the game mine where they mine phosphate ore since, oh gosh, I think the forties, and maybe even before that. And the game mine site is actually within the boundaries of the reservation and that’s actually on the national priorities list. But that’s about the south to us. But when you go to the north of us and our ancestral lands, you have the Idaho National Laboratory and Department of Energy reservation, and that’s about 50 miles, a little less than 50 miles north of our boundary.

Kari Hulac (06:24):

Yes, I’ve definitely wanted to ask about the relationship with the Lab. So this is a great segue here, you know, what is your relationship with the Lab and how do you feel – has it been responsive to tribal input and concerns? What are some of the issues that you deal with being in that location?

Talia Martin (06:43):

Right. You know, I think it’s best to understand some of the history between the tribes and DOE, the Labs. So when I say the tribes, I mean the Shoshone-Bannock tribes. The Idaho National Laboratory sits on ancestral lands and so I mentioned earlier that the tribe is actually composed of two tribes: Shoshone and Bannock, and we’re descendants of both tribes put on one reservation. But the ancestral lands, there’s evidence that our ancestors had used it as a transportation quarter, has also used it in other ways, you know, whether it’s ceremonial. They inhabited those areas at different times of the season. So it has ancestral value, significant ancestral value to the tribes. Of course now we’re one tribe, Shoshone-Bannock tribe, so not a lot of people know that, but some of the culturally significant sites that are on there are ceremonial.

Talia Martin (07:54):

Some are to do with the landscape there, like the view, the caves, there’s a lot of volcanic activity in that area. So there are some caves that were in use by some of our ancestors. There’s also hunting and gathering areas that the tribes had been able to use prior to the INL placing their site there. So there’s quite a bit of use that the tribes had used it for prior. And so we have inherent rights to the ancestral lands where INL sits. So I’m kind of fast-forwarding to the future here around 1992 or close to the nineties and a little prior before that the tribes said have seen shipments coming on the interstate, which the interstate goes right through the reservation. And a lot of these shipments had to do with spent nuclear fuel, transuranic.

Talia Martin (08:57):

There’s also a railroad that goes through our reservation, and those are actually transuranic shipments from the Department of Defense from nuclear waste or spent fuel from submarines that use nuclear reactors. So a lot of that was being shipped through our reservation to the INL site, without any type of agreement, input, any type of tribal involvement during that time because the tribes are a sovereign nation, self-governing. There was a responsibility for the Department of Energy as well as DOD to confirm and work with the tribes because they’re going directly through the tribal lands, but also due to ancestral lands that they committed and obligated to be protective of. So that 1992 tribe had put a Fort Hall police department, they parked a vehicle there on the railroad and block transuranic shipments, which forced DOD and DOE to work with the tribes and come to some type of agreement.

Talia Martin (10:09):

And out of that came a working agreement around 1982 and there was a series of agreements from there that just, you know, continued to renew. They provided funding so that the tribes could work with DOE and DOE could provide personnel to make sure that they’re monitoring any DOD activities. Hence, this is where tribal DOE came out of. And the main objective was to monitor cultural resources that were on the INL site, environmental resources, natural and cultural. So we’ve had a working agreement for over 25 years with DOE and they’ve helped the tribes to manage and to be involved, you know with DOE in anything they might be doing as far as cultural resources management, environment management. But the primary focus of the tribe’s work with the DOE is on making sure they’re protecting the Snake River Plain aquifer, which is, you know, the sole source aquifer in this region. One downside to that is the tribes don’t have any regulatory oversight like the state does. Idaho Department of Environmental Quality – they regulate environmental regulations, and we’re able to work with IDEQ and DOE to make sure that the information that they’re collecting and providing is true and kind of give us assurances and confirmation that we’re receiving information, the right information.

Kari Hulac (11:49):

So you touched on transportation being a large issue, obviously, that sounded like a struggle that you overcame. Are there other nuclear waste issues that you’re working on, or would you say transportation is the main piece that you have to monitor and work with?

Talia Martin (12:08):

Yeah, I would say that transportation is one of the major issues, you know, shipments going to WIPP, spent nuclear fuel shipments coming to INL for research. But also we do a lot of environment monitoring specifically in this office. And we have technicians that work with USGS to provide groundwater monitoring or staff to work with USGS to provide groundwater monitoring. We also have technicians that will work with cultural resources when they’re on the site, they do a lot of cultural resource survey if there’s land that will be disturbed by any type of construction or cleanup activities. We have cultural resources staff from the tribes that will work with Battelle Energy Alliance with contractors from INL that actually operate the INL site. They’ll work with them doing surveying and making sure there aren’t artifacts or anything that is relevant to the tribes, that they’re protected. And they follow the cultural resources management procedure that is in alignment with what the tribes have put input into.

Kari Hulac (13:24):

So would you say overall that you’ve seen progress? Do you feel optimistic for that relationship?

Talia Martin (13:31):

You know, gosh, I honestly, I’m relatively new for six years, but we do see some cycling of the same patterns and work. The tribes are always enforcing and trying to maintain consultation between DOE and the tribes and, you know, with DOE’s some internal rehab where we’re re-educating some of the staff to ensure that they are updating and getting input from our Fort Hall Business Council and, you know, our governing body. But we really rely on the trust responsibility of the Department of Energy and make sure that the consultation is meaningful and timely. And sometimes we’re not always seeing it, except when it has to do with the regulatory drivers, such as NEPA, which is the National Environmental Protection Act. When there’s public commenting going on, there’s usually, they’re very good at maintaining that checklist. Making sure that they’re following the schedule and getting the input as far as concerns being addressed.

Talia Martin (14:40):

I think it really depends on case by case, especially if there’s a regulatory driver, then the state is very much involved in and they’ll take our concerns. You know, it’s kind of, it’s an interesting place we would find ourselves in when, you know, they take our concern and information, and it’s well-documented. And it’s not always the type of consultation that we expect. We, again, want it to be a meaningful two-way dialogue, then addressing concerns. And sometimes you get that, sometimes you don’t, and we’ve seen some progress and sometimes we do take a couple steps backwards. But that working agreement has done pretty good as far as making sure there’s communication. Can there be improvement? Absolutely. You know, on both sides and no matter who we’re talking about, whether it’s our tribal staff and making sure we’re maintaining the presence on the site. The DOE, making sure that their tribal liaisons are informing and updating, and notifying our governing body to make sure they’re addressing those concerns. So we’re always enforcing consultation and I really do see some improvement and need for improvement as well.

Kari Hulac (16:06):

So the nuclear waste disposal situation is at an impasse right now in the US as you well know Yucca Mountain in Nevada. The situation there, do you have thoughts about the primary reasons for this? Is there a vision that you’d like to see happen for moving past that and finding a solution?

Talia Martin (16:27):

This is an interesting question because you can get the typical response about the political issues that the geological repository has brought up, the legal challenges, the licensing activities, and from tribal perspective, you know, you see some social barriers from the communities themselves. And so what’s interesting is in 2015, when I first came on consent-based siting was a major approach they were using, and considering at least to help drive an approval for a geological repository. It went away with the next administration, and then when we went full circle to consent-based siting again, and it’s worked for some areas like you know, up in Canada, I think there are some areas where it’s actually worse even with the indigenous population. But there’s still questions. You know, this is a great approach, but there’s still questions from the Indian tribes that are actually affected by the location of the proposed geological repositories.

Talia Martin (17:40):

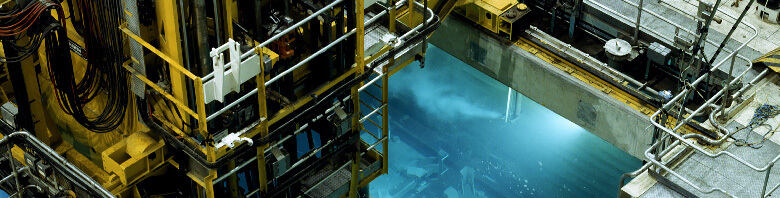

Another interesting part of this is we’re still generating nuclear waste. Commercial reactors are still operating. And to this day on the Idaho National Laboratory site, we have siting nuclear reactors for the advanced reactor mission. And we, one of our major concerns is the fact that the nuclear waste or the spent fuel that will be generated has no place to go, no home. You know, once after the cooling process of course, it goes into wet storage and has to be stored somewhere else, or I guess you call it disposal of the waste. So right now we’re seeing interim storage, which was something that was predicted decades ago by many, many proponents and opponents of the nuclear waste issue. So we’re seeing interim storage at the sites of the reactor sites and from the advanced reactors we’re hearing of – there’s definitely a huge push for interim storage at other areas where there are tribes within those places.

Talia Martin (19:02):

You’re still gonna have to have that engagement with these tribes in some way. What’s another interesting part of this is that private federal partnership where you had advanced reactors and a cooperative agreement between DOE and that private company. So where do the tribes fit in? It has always been a question that is not entirely been answered by DOE nor by the company. And we’re starting to see some of their licensee applications go through where we don’t consider that they’ve done a thorough job of cultural resource and environmental impacts that can occur. And so we’ve had a late tribal input. So we’re still open to this discussion and we’d like to be, all tribes would like to be engaged upon if we see any type of federal actions or activities that could impact tribal interests.

Kari Hulac (20:13):

And I know this is a huge challenge for many Native American reservations across the US. Those lands are often near these types of sites or are often targeted for disposal. We do feel if the consent-based siting process is properly followed that, you know, are tribes that you’re aware of open to hosting disposal or storage sites?

Talia Martin (20:42):

Some of our tribal working groups, you know, we play around with that same question and challenge if their tribes open to this. And, you know, we have different representatives on these working groups because there’s so many viewpoints that are valid, you know, in their area of interest and their locations and that the DOE sites they work with. So like generally speaking tribes have been involved in this discussion and nobody has closed their doors to being involved at least in the discussion of consent-based siting process, because that process is still up in the air on how that is going to involve Indian tribes and we’re still asking that question. There has been some history as far as tribes were involved in the monitoring, retrieval, storage, but there was some pushback from the state itself. So, you know, if you reverse that and state is actually the ones that consent to it, you know, where are Indian tribes? Were they allowed to voice their opinion and have their concerns addressed adequately is a question. So are we open to these questions, to the process? We have been in the past. So I think it’s really up in the air. You know, it’s kind of open-ended right now.

Kari Hulac (22:15):

How have you approached your role in a way that’s helped you be successful interacting with such a wide group of stakeholders?

Talia Martin (22:23):

One of the biggest strengths I think in working with federal agencies and state and the tribes is being able to be involved in relationship building as well as maintaining communication is vital. And again, we talk about two way dialogue and enforcing it and sometimes the tribes, they feel that they’re being spoken to rather than listening as well. And so at this level, we really have to work at the staff and technical level. We really have to work on our communication skills to make sure that everybody is heard in the room and our tribes issues and concerns are addressed as well.

Kari Hulac (23:04):

Anything I didn’t ask so far that you’d like our listeners to take away from our conversation?

Talia Martin (23:10):

You know, you did kind of allude to it. We talked a little bit about STGWG and I’m not doing any type of shameless plug, but I, you know, this group is it’s been around a long time and they’ve had a lot of great accomplishments and instrumental in working with the Office of Legacy Management, in helping to advocate for the formation of the long-term stewardship working group. And that’s because one of their two priorities is long-term stewardship of the cleanup sites. Once the work is done, clean-up has occurred, remediation, these sites will go into long-term monitoring to ensure that they remain protected. One thing you might hear from tribes is the reservation, the people, they’re not going anywhere, we’re connected to the land, and even after the DOE leaves and the other federal agencies that might’ve been there and they leave, we’re going to continue to be there.

Kari Hulac (24:12):

I think touching back, just to kind of follow up on a question I asked earlier I mean, does the tribes that you work with have a wish for what happens to the waste, or you don’t take an opinion on that at this point, or, you know, you’re just kind of managing the tribal interests, like for example, the transportation going through, You have kind of a perfect world, like a wish you’d like for a final resolution?

Talia Martin (24:44):

Right. Well, at the Idaho National Laboratory, there are two different offices there, which is NE, Nuclear Energy, and then Environmental Management, and the tribes understand that they’re always going to have a research mission there, and that’s important to them. And sometimes we will have shipments that go through the reservation that have to do with nuclear materials or spent fuel that they’re researching on. We’ve had, we like to stay involved in those conversations, you know, because it continues to go through the reservation on transportation corridor. As far as the cleanup mission goes, the state of Idaho, the tribes, we’ve all agreed on one thing: that you don’t want there to be perpetual waste up here is something you hear often. And so ideally we would like the waste, the by-products and materials from the waste to be shipped out. You know, there’s a lot of other types of waste that have come from other sites like Rocky Flats, Three Mile Island that are being stored here. And so we continuously say we want that out. And that would, of course, be the ideal world.

Kari Hulac (26:05):

And when you say out, do you have a destination in mind?

Talia Martin (26:10):

We don’t have to have a destination. You know, we don’t wish upon waste to be involuntarily put on someone else, but we definitely don’t want it on our ancestral lands, on our tribal lands. I mean, this is part of our preservation of our culture and in our practices or traditions. So we’re constantly working hard, our cultural resources staff work very hard to protect those resources, whether it’s as special as on INL site or in sister lands, you know, in Montana and Colorado area where we’re constantly working to protect and preserve our culture.

Kari Hulac (26:54):

Thank you. Well, thank you so much for joining me today. Talia, really appreciate it.

Nuclear Waste 101

Understand more about nuclear waste and its implications for you and your community.

FAQS

Deep Isolation answers frequently asked questions about our technology, our process, and safety.