Episode 15

Tom Isaacs

Co-Principal Investigator at the Nuclear Threat Initiative

How to Build a Successful Nuclear Waste Disposal Program

In this episode, Tom Isaacs gives historical insight into nuclear waste disposal barriers internationally and explains how those barriers can be overcome by using both social science and hard science.

Note: This transcript is the raw transcript of this podcast. Minimal edits have been made only for clarity purposes.

Tom Isaacs (0:10):

I would say the first one is that this is a problem that’s solvable. That we know, we, the scientific and technical community know, and in fact, every country around the world who is seriously dealing with this, knows how to dispose of this waste in a way that is permanent.

Narrator (0:30):

Did you know that there are half a million metric tons of nuclear waste temporarily stored at hundreds of sites worldwide? In the U.S. alone, one in three people live within 50 miles of a storage site. No country has yet successfully disposed of commercial spent nuclear fuel, but it’s not for lack of a solution. So what’s the delay? The answers are complex and controversial. In this series, we explore the nuclear waste issue with people representing various pieces of this complicated puzzle. We hope this podcast will give you a clearer picture of Nuclear Waste: The Whole Story.

We believe that listening is an important element of a successful nuclear waste disposal program. A core company value is to seek and listen to different perspectives. Opinions expressed by the interviewers and their subjects are not necessarily representative of the company. If there’s a topic discussed in the podcast that is unfamiliar to you, or you’d like to more closely review what was said, please see the show notes at deepisolation.com/podcasts.

Kari Hulac (1:52):

Hello, I’m Kari Hulac, Deep Isolations Communication Manager. Today I’m talking to Tom Isaacs, an engineer and physicist with a great deal of experience in nuclear policy analysis. He is co-principal investigator for the Nuclear Threat Initiative. Tom works with NTIs Developing Spent Fuel Strategies Project coordinating international cooperation on issues at the back end of the fuel cycle with emphasis on spent fuel management and disposal in Pacific Rim countries. He also advises national nuclear waste programs on facility siting, communications, stakeholder engagement, and public trust and confidence. He’s worked with the Canadian Nuclear Waste Management Organization for 15 years. And in 2012 was Lead Advisor to President Obama’s Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future. He’s a long-time Senior Executive at the Department of Energy where he led the siting process for establishing a deep geological repository at Nevada’s Yucca Mountain. Thank you so much for joining us today, Tom.

Tom Isaacs (02:57):

Thank you very much. I appreciate the opportunity.

Kari Hulac (03:00):

We like to start out by asking our interviewees, how did you choose a career in nuclear waste? What first got you interested in dedicating your career to such a complicated and controversial topic?

Tom Isaacs (03:12):

Yeah, that’s a good question. I’m not sure I know the answer myself. I had started working on nuclear energy development in the Atomic Energy Commission in the old days, and then left the government of DOE what became DOE for a while and got a phone call from someone in the mid-eighties who said, there’s a new law passed and we’re going to create a nuclear waste organization and the Department of Energy and I’d really like you to come work with me. And that person’s name was Ben Rusche, a wonderful human being. And he was the first Director of what was called the Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management. And so the opportunity to work with Ben on this issue presented itself. And so I came back into the Department of Energy as the Director of Policy and found that the problem was really fascinating because you’re at the cutting edge of science and technology all the way through to thinking about things that are essentially almost spiritual in nature because you’re dealing with waste that is going to be potentially hazardous for as long as you can think of. And so the gamut of experiences dealing with the science, dealing with the public, dealing with the politics, dealing with how human beings should responsibly deal with this all kind of fit with my interest in these sort of multifaceted problems. So that’s kind of how I got into it. And once you get into it, it’s hard to get out of it.

Kari Hulac (04:40):

Well, that’s fascinating, especially the part about “spiritual”. I haven’t heard that term used with nuclear waste, but essentially it’s so far off into the future. You don’t even know what the planet will look like, or humans will look like or anything.

Tom Isaacs (04:54):

Exactly. Almost anything you can think of, this waste will be around after that’s gone. And that’s an interesting problem. And fortunately, I’m sure we’ll talk about this. I think there’s ways to deal with that.

Kari Hulac (05:06):

Perfect. So, since you have been in the business for 35 years, we’ll never touch on everything today. So I wanted to just ask you what are three big things that you’ve learned over that time that you think the general public should know? Like what would you just like, if you could leave three takeaways from your experience, what might they be?

Tom Isaacs (05:27):

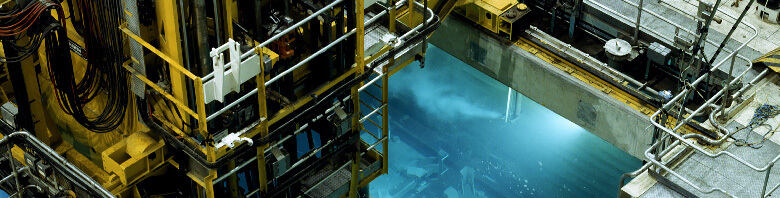

Well, let’s see, I would say the first one is that this is a problem that’s solvable that we know, we, the scientific and technical community know, and in fact, every country around the world who is seriously dealing with this, knows how to dispose of this waste in a way that is permanent, that doesn’t require active administrative control for eons. And that will guarantee that the waste will not come back into the accessible environment during the time in which it’s hazardous. So I think that’s very important. The second thing corollary to that is when we talk about disposing of nuclear waste, we’re not talking about a nuclear dump. If you hear somebody use the word dump, they either don’t understand, or they deliberately don’t want people to understand. This is a very highly engineered facility that’s deep underground.

Tom Isaacs (06:15):

The waste is solid, there’s nothing but solid waste. There’s no liquids or gases or anything. It’s put into a very carefully designed and constructed container to isolate the waste and then put underground only in a place where it’s going to isolate the waste for geologic time periods. And so that would be my second takeaway. And the third takeaway is it’s really hard to find a way to site these facilities. That’s the key issue is developing a narrative, which probably hasn’t been done well yet, to make people understand the true nature of this problem in a way that will allow local communities, surrounding communities, regional communities in the United States, state government, which is a particularly difficult challenge, and the federal government, and the local populations that are involved; for all of them to come to a place where it’s viewed as what I call a win-win-win situation for them. And I think those are the three things I would say are the main reasons that the next generation should come in and work on this problem.

Kari Hulac (07:24):

Well, I think the next question will help tie into some of the points that you made there because as you well know, scientists worldwide have agreed for decades that the waste does belong in deep geologic disposal, yet to date spent nuclear fuel remains in temporary storage. So maybe you could talk about your perspective on that problem. What would it take for permanent disposal to finally happen?

Tom Isaacs (07:50):

Sure. So let’s talk internationally first because there’s some good news there and that’s that there are countries that have made substantial progress. I would highlight Finland and Sweden as probably being the leading countries in the world, in terms of developing and implementing a program to dispose of the spent fuel. They went through a very vigorous siting program in both of those countries. They were able to establish agreements with local communities to site a nuclear waste repository in Finland. They are in the process now, they’ve received the license and are in the process of constructing and operating a license. And that’ll be what I call the existence proof. It’ll show you that it is possible to do that. And I expect in the very near future, Finland will be operating a nuclear waste repository and disposing of spent fuel. I think just somewhat behind that will come Sweden.

Tom Isaacs (08:45):

That’s also extremely far along in this process. So there’s a lot of lessons to be learned in those countries. France as well, has a site under developments as well along and looks to be good. And the Canadians, as you mentioned, that I’ve been working with for quite some time and continue to work with have developed an approach. They call it Adaptive Phase Management, which has taken to heart many of the same recommendations that were in that Blue Ribbon Commission report that was done that I was Lead Advisor for under President Obama that proposed a roadmap forward for how the U.S. should go about disposing of spent nuclear fuel. So I think there’s some very good lessons there. The US has a particular problem. Other countries have problems too, almost all countries do. And almost all countries have to take long periods of time and have lots of changes before they’re successful.

Tom Isaacs (09:42):

But the US has states. And if the federal government could deal directly with local communities, it would be possible, I’m quite confident to site a nuclear waste repository in this country. There are communities who would be interested in, are interested and have shown interest in the past in these kinds of things. Even the elected county commission in Nye county, which is where Yucca Mountain was, was in favor of this program at that point in time. So I think you can find that, but it’ what’s often called the donut effect. The people closest to the repository site are in favor of it. They see the jobs, they see the economic benefits. They see the world-class scientists and technical people coming to the site. They see the notoriety, they see lots of positive things for their community, not all communities, but you only need one. People who are far away who are actually hosting the site with the nuclear waste now, which is mostly nuclear power plants, also are in favor of these because they want to see the waste taken off in their sites.

Tom Isaacs (10:43):

It’s the donut, that’s the problem. It’s the people in the state that you’re thinking of who are not close to the site, but in the state, who see this as potentially environmentally a concern, potentially a safety concern, they don’t see big economic benefits for them because they may be hundreds of miles away. They see possible stigma effects as a result of being the state that hosts these kinds of facilities. And so it’s at the state level that you find state elected officials, both governors and other state elected officials, as well as people in Congress, who have tended to be the ones who have resisted siting in their states mostly. And that’s the big challenge, the biggest challenge, there’s many challenges. That’s the biggest challenge I would say, is changing the narrative that people, so that people understand that for certain communities, this can be an enormous benefit to them and can help them realize the future that they would like. And we’ve seen that in places around the world, like in Olkiluoto Finland, for example, like in New Mexico, where there’s an operating repository for defense waste, where the community has been very much in favor of that and benefited from it. And I think continues to be interested in seeing the mission of that repository expanded.

Kari Hulac (12:05):

So there’s so many things to talk about here. I definitely, there’s kind of three main things that will tie off of what you just said. Well you just mentioned New Mexico so let’s touch on that. That’s the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in Carlsbad where certain types of defense-generated waste: clothing, tools, rags, residues are disposed of. So what can be learned from WIPP since that is in the U.S., and we have Yucca Mountain, which is on hold at the moment. So what have we learned from WIPP and how might this relate to deciding a facility for spent nuclear fuel?

Tom Isaacs (12:43):

So I think that’s a great question. I think there’s a lot to be learned from WIPP. So let me give the short, my short version of how WIPP came about, because the town that hosts the WIPP site is called Carlsbad, New Mexico. It’s fairly isolated in Southern New Mexico, and it was a largely potash mining town. And as mining happens, it goes boom and bust, it went bust at a period of time. And the economic engine for the community of Carlsbad was in serious scrapes as a result of that. Some entrepreneurial people, elected representatives and other people in that region learned that the federal government was trying to find a place to site for nuclear waste disposal and went to the government and said, we’d like to learn more about this. We’d like to see if this is something that would work for us. We’re a mining community.

Tom Isaacs (13:39):

So we’re used to putting holes in the ground. We understand that kind of thing. Would you consider us? That was the beginning of a very long and unexpected process. You know, the Canadians called their process Adapted Phase Management because you have to adapt because the length of time it takes for a program like this to be implemented is decades and things change over time. Science changes, technology changes, political views change, values change, economics change. And so you have to be willing to adapt. And so the process that went forward started with this process, and immediately there was resistance from people within the state of New Mexico. In particular, I would say from the cities far away from Carlsbad, like Albuquerque and particularly Santa Fe, the state capitol, you would go to Santa Fe and you’d see signs there with WIPP with a red circle and a line through it.

Tom Isaacs (14:36):

They didn’t want WIPP in their state. There was a long period of engagement and to their credit, the federal government understood that they needed to engage in a way that would lead to ultimate acceptance. At the state level, there was concern by the governor and other state elected officials that spent nuclear fuel would come into the state of New Mexico. There had been a pilot facility where they had done research and so forth. And so at the state level, the federal government reached an understanding with the state government that in return for allowing WIPP to go forward, no spent nuclear fuel would go into the state of New Mexico into that facility. Only defense waste. The defense waste is radioactive. It’s radioactive for very long periods of time, which is why you have to dispose of it deep underground in a repository. It’s not hot and it’s not nearly as concentrated as the spent nuclear fuel.

Tom Isaacs (15:34):

So what you wound up with what I call the win-win-win. When the local people got the facility, they got tremendous benefits from it in terms of jobs, in terms of economic support, in terms of the hopes and visions of the community being resuscitated, the state government got and promised that spent nuclear fuel would not come into that facility. And what else they got was a bypass around the city of Santa Fe. It was very interesting. If you think about it, who would have thought that this program would hinge on the federal government paying for a bypass road around the city of Santa Fe? A lot of the waste was coming from Idaho which would come through Santa Fe. And because there was no bypass, the waste would’ve come through the city. And the people were understandably saying, we don’t want this waste coming through the middle of our city.

Tom Isaacs (16:24):

So one of the agreements was that the state of New Mexico won, if you will, a bypass built around the city of Santa Fe. And of course the federal government won because they were able to establish a repository which has been operating for over a decade and disposes of this transuranic defense waste. So that’s what I mean by win-win-wins. Ironically, by the way, a lot of the development in Santa Fe over the last 10 plus years has been near that bypass around Santa Fe, even though it was built so that people could move themselves from the waste. People understand that the, I think, that the transportation is very safe, it is very safe, has been very safe. And so they’re willing to move near the bypass, even though it was built as a reason for sort of moving people away from it,

Kari Hulac (17:13):

Like an incredible amount of negotiations that must gone on like about just, you know, kind of working it out. So everyone, like you say, so everyone involved felt like their issues were addressed. I mean, that seems like a huge learning from that. It sounds incredibly adaptive, which you’ve mentioned that term a couple times, Adaptive Phase Management. So it sounds like there’s a lot to be learned there.

Tom Isaacs (17:36):

I think that’s right. I gave you my, what I call the reader’s digest version of what happened, what happened there took place over many, many years with lots of disagreements with lots of one step forward, two steps back with changes of people in positions of influence, but in this case, and this was another lesson learned, it was a small number of people who were highly motivated and highly competent and well-intentioned who wound up making a big part of the difference. The people in Carlsbad are to be applauded for having had the initiative to do this. The scientists who worked on this program, many of them from Sandia National Laboratory in New Mexico did world-class science, but also understood how to engage with local communities in a way that respected them and responded to them. The federal government, to its credit, funded this program properly, was willing to do flexible things that you wouldn’t necessarily think at the beginning of a project would be important in order to make this happen. Right?

Tom Isaacs (18:46):

So I think there’s lots of lessons to be learned. And if you went to these other countries that I’ve mentioned, you would find equally interesting histories of how those facilities came about. They also had problems in the beginning. They also had resistance in the beginning and they also made adaptations in order to meet the needs and concerns of the involved citizens and of the people who would be affected by this, both at the facility, and along transportation routes, and because people are concerned legitimately about health, environment, and safety. So I think all of that is what made me get interested in this problem and stay interested in this problem.

Kari Hulac (19:27):

So I have to now ask about Yucca Mountain, because I guess if you could have the stark opposite of Carlsbad, I don’t know if Yucca Mountain would be it in your opinion, but plans that would house the U.S. spent nuclear fuel is currently not moving forward. So what can we learn maybe by comparing the two cases, maybe you cannot compare them? I’d love to hear from you about that and what should the U.S. government do to restart its spent fuel disposal program.

Tom Isaacs (20:00):

Yeah. So first of all, as we speak today, I would say Yucca Mountain is stopped and there there’s no prospect for restarting with the current, with the mission it had disposing of spent nuclear fuel. The Blue Ribbon Commission looked at this in great detail, obviously when it decided to come to make the recommendations. It did that. I would say the first issue with the Yucca program was that the law that was passed in 1982, almost 40 years ago and signed into law in 1983 was extremely prescriptive. It, for example, grandfathered in nine sites in six states that were to be the only candidate sites for being a geologic repository. And they were chosen strictly based on the scientific potential to isolate the waste, not on the interest or the willingness of the communities near these sites to be a host, not based on the willingness of a state government to tolerate this in their state.

Tom Isaacs (21:06):

They were picked because there had been a scientific survey and these look promising. So the way the law was set up, it was to do a kind of a beauty contest to investigate these nine sites and sequentially eliminate the sites until you ultimately had three of the best looking sites. And then you would characterize them, which meant years and years of scientific investigation, and then figure out which one looked best. And that’s the one you would pick whether or not the people nearby these sites wanted it or not. It was what some people used to call “decide, announce, defend.” You would decide something you’d tell people, and then you’d defend it against people’s concerns. And that didn’t work very well. In fact, the communities around all nine of those sites were not pleased at being put on this list without having been asked, whether they’re willing to accept that or not.

Tom Isaacs (22:06):

So I think that was a real issue. Then you had the enormous problems of politics that were associated with this at the federal level. It was not so much the Democrats versus Republicans or the House versus the Senate. It was more east versus west, in a way. Most of the nuclear waste, 80% of it in this country, spent nuclear fuel is east of the Mississippi River. Most people expected this repository to be west of the Mississippi River because that’s where a lot of the remote land was. And so that set up a problem. That problem was solved in the nuclear waste law by saying, all right, we’ll build not one but two repositories and you should build the second one. The code language was basically put it in the east if you’re going to build the second one, first one in the west.

Tom Isaacs (22:57):

So now you had this issue of building a second repository and looking for sites in relatively highly densely populated areas, which was also extremely difficult. So now we tried to follow the law. We created nine environmental assessments. Each one of those assessments was over a thousand pages long, really detailed assessments of these sites. And like the law said, and the law had dates in it and the dates were extremely ambitious, really. So it didn’t allow for a lot of discussion or negotiation. It was, you got to do this and you got to do it. And Congress did that on purpose so that the program would have momentum going forward. They didn’t want these problems to stop. And in fact, they gave the governors what was called the right of a notice of disapproval, essentially a veto in the law because they knew wherever they went, the governor was going to probably say no, but then Congress had the right to override that veto with a vote, a majority vote in both houses within 60 days.

Tom Isaacs (24:00):

So it was all set up for controversy, not for negotiation and collaboration. And what happened was the politics got so heated that in the depths of the winter, in Washington in 1987, Congress made a decision to truncate that law and said, we’re not going to look at three sites. We’re going to just pick one of the three. And they picked Yucca Mountain. Yucca Mountain, it has to be said, many people don’t know this, at that point in time was the most promising site based on our science. So it’s not like we were picking an inferior site. Later, we found that there were complications for Yucca Mountain, but it looked like a very promising site. It could probably still be a promising site from a scientific point of view, but people felt like that that rope, the bond that was tenuous to begin with of trust, if you will, that they were going to go through this process and at least pick sites based upon this hierarchy that had been laid out in the law so people in Nevada had been upset in against the program before this decision, they were more upset and more intensely opposed after the decision.

Tom Isaacs (25:15):

And so from a political point of view, they did everything possible to keep that program from going forward. And politics played a role in that program. And there was a Senator from Nevada, Harry Reid, who was very influential at that point in time in Nevada. And he essentially worked with the administration to stop that program. And you can argue whether it was a right decision or wrong decision, but it was the decision. And that program was stopped and has been essentially endorsed to be continued to be stopped ever since. And I don’t see any prospect anytime soon for that changing, even though, as I mentioned it, people around there, there aren’t a lot of people, I kid that Yucca Mountain is not the end of the earth, but you can see it from there. I mean, it’s really remote, but there are people in towns, you know, not too, too far away and those people are not as exercised about this cause they could see potential benefits. But the people, for example, Las Vegas or Carson City adamantly against it and for understandable reasons.

Kari Hulac (26:24):

So what’s next? What should the government do to restart its waste program in the U.S. Is there any hope moving forward?

Tom Isaacs (26:32):

I think there is hope. I think if you get in the waste business, you’d better be an optimist, but, you have to be a realist too, but if you’re not an optimist, you’re probably going to be unhappy. The Blue Ribbon Commission, which is now, you know, almost a decade old, still is the go-to document in my view, in many people’s view, for recommendations about how to restart the program. And it had eight principal recommendations. So I won’t go through all eight with you, but I will go through a few. And this commission by the way, was bi-partisan it was chaired by a prominent Republican and a prominent Democrat.

Tom Isaacs (27:05):

And they worked together extremely well and they came out with eight recommendations and the first was we should use consent-based siting. Don’t pick a site and then try to convince people they should want it. Start by looking for where communities express interest that they can benefit potentially from this. And start by asking them, would they be interested in learning about this process? Would you be interested? With no commitment on their part at all, but would you be willing to sit down and listen in and talk about this and begin a dialogue with them and learn what their interests are, what their hopes for their communities are, what the problems in their communities are, how can this program help them? So consent-based siting was probably the most important recommendation. And there’s good news that as we speak, I think the current administration and Secretary Granholm have indicated they would like to restart the program and they understand it should be done in a consent-based way.

Tom Isaacs (28:02):

Two other very important recommendations were, and this word I’m about to say was discussed greatly during the Blue Ribbon Commission, the word is prompt. We should promptly begin work on developing interim storage facility and we should promptly begin working on the development of a permanent repository. We need both of those things. We need an interim storage facility, particularly since a number of nuclear power plants in this country have shut down and the waste that’s sitting on those sites and they can’t decommission the sites until there’s a place to send the waste. And the repository program, as we’ve already discussed is going to take many decades. You can build an interim storage facility in a much shorter period of time. It’s a more straightforward facility. It has to demonstrate it will work for decades, not for millennia. And we ought to be able to do that. And that’s a siting issue as well.

Tom Isaacs (28:57):

And part of the siting issue is people who will host an interim storage facility want to know that there’s going to be a repository someday to take that waste away. So that’s why you need to do both of those things. So I would say that’s the bones of the program is that you need a program that will use consent-based siting, that will hopefully have the kind of expertise and skill set that is necessary because it’s not just scientists. It’s a variety of types of people who can appreciate and empathize and work with and negotiate through this multifaceted problem that we’ve discussed already. So I think that would be the bones. The other thing that’s really difficult that the Blue Ribbon Commission recommended, and this is I think, a really stretch goal is it should be made an independent organization dedicated to this mission alone.

Tom Isaacs (30:00)

It is that way in every other country in the world, it’s not part of a cabinet level department. It has a degree of independence, if you will. It still needs to be overseen by Congress. It still needs to have its budgets supplied. But when you have a program that is so fragile with each coming election, it makes it very difficult for people to have confidence that they can believe what you say, because you may be in charge of the program one day, an election comes along, there’s a new Congress where there’s a new administration and are they going to have the same view and are they going to be willing to carry on the program that the last administration committed to? And the answer has been no up until now in this country. And so we need to find a way to, I’ll use the word, buffer this from the day to day short-term political considerations. And unfortunately in this country, that’s really difficult.

Kari Hulac (30:58):

So let’s talk about your work with the Canadian Nuclear Waste Management Organization, because they’re having more success. You’ve worked with them for more than a decade. What are some reasons it has been successful? And what can we in any other country learn about nuclear waste disposal from Canada?

Tom Isaacs (31:15):

My first comment would be that they have implemented a program that is very similar to many of the recommendations of our Blue Ribbon Commission. So that it literally reflects some of the work that’s gone in Canada. Canada had a nuclear waste program. When I was in the Department of Energy, I used to work closely with them, and that program was stopped cold around, I think the year 2000, perhaps, when they had an independent commission that said from a scientific and technical point of view, this program is good, but from a public safety point of view, from a public acceptance point of view, it’s not adequate.

Tom Isaacs (32:00):

And they literally stopped the program, took it out of government, created the Nuclear Waste Management Organization as an independent entity. Like we just talked about. It is funded and the board of directors is drawn largely from the waste producers so they have an incentive. It’s overseen by the Canadian government, but not with the level of hands-on detail that we find in the United States. So that would be the first thing is that you have to have a construct that allows a program like this to be successful. They immediately decided that they would go with a consent based approach to this. And so they started by asking for expressions of interest from communities to learn about this. And they had 22 communities from throughout Canada, say, we’re not committing to anything, but we’d like to learn about this. 22 communities. And I have visited most of those communities.

Tom Isaacs (32:58):

Many of them are small and very remote. It’s pretty exciting to go to some of these towns in far off places with wonderful people in them. And they did a sequential process of narrowing 22, and they did it by looking both at the scientific promise of the sites near these communities to isolate the waste. And by looking at the soft science part of this, the willingness, the degree to which this program can help these communities help themselves, to can provide these communities with this kind of resource. So many of them, by the way, were ex mining communities or forestry communities, which experience again, this boom and bust cycle. And in a lot of cases, some of these communities felt like their future didn’t look very good, and the young people were moving away and they wanted to revitalize those towns. And so over a period of time looking at both the hard science and the soft science and engaging with these communities in a very extensive way, they narrowed down the sites because ultimately they need one.

Tom Isaacs (34:03):

And so they have gone through this process and they are now down to two sites that are the final candidate sites. One is in a place called South Bruce near where a lot of the nuclear power plants are. And another one is a town called Ignace, which is a relatively small town farther west than Ontario. That was another provision they said, because the nuclear waste was almost all in the province of Ontario they would put preference on siting in the province of Ontario from an equity point of view. Fairness mattered a lot, it matters a lot to the Canadians. And I think that that’s another lesson learned to really walk the talk of being fair in all respects and they actually had a fairness round table, a group of experts, if you say, in this kind of issue to provide advice to them on how to think about being fair.

Tom Isaacs (35:00):

So they called it an ethics round table. But it was really about being fair and there’s no guarantee as we sit here today, that there’s going to be a repository of either of these two sites, because neither of them had yet agreed to host the site. The Nuclear Waste Management Organization has said they would like to pick a final site by 2023 so that’s not very far off. And they’re going through negotiations now and scientific investigations now, and looking at all the factors that will have to be put in play. And the one additional factor that’s very important in Canada is relations with the indigenous population. It’s very hard to find any place in Canada where indigenous people don’t have a history and rights.

Tom Isaacs (35:49):

And it is the case in both of these locations and Canadians when we talk about fairness, they take that very, very seriously and have really been about as cutting edge in terms of trying to understand and have the relationships with these indigenous organizations and individuals as they possibly can. So that will also play a large role in the site selection process. So I would say that those are probably the lessons learned, these programs often are run by scientists and technical people and science. You know, when you run a project, you think about cost, schedule, and content. You wanna, you know, go fast and you want to spend the least amount of money, and you want to get the project built. And in this case, I often tell people, my advice is go slow to go fast. And what I mean by that is you have to take the time and be willing and actually care about these other aspects of affecting people’s lives in a sincere way if you’re going to get their trust and cooperation. And that’s you mentioned earlier my background, I spent a lot of time thinking about public trust and confidence and how to achieve it, because I think that’s essential and it’s something that’s been very difficult and probably more difficult with passing time in this country, as we’ve seen.

Kari Hulac (37:23):

Just a couple of questions left here today. Tell us about your work on the Nuclear Threat Initiative. That’s, DC-based correct?

Tom Isaacs (37:33):

Right. The Nuclear Threat Initiative now called NTI is an NGO based in Washington DC. And it has worked on a number of nuclear related and other security related issues over time. And the project that we have brings together nuclear waste organizations largely around from the Pacific rim who have interest in common in dealing with nuclear waste. So we’re talking about countries like Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Australia, Canada, the United States. China has been part of it at times. We’ve brought in people from international organizations like the IAEA in Vienna, and the NEA and Nuclear Energy Agency in Paris. And we also invited other countries that are interested as well. And the idea is to come together and say, so what’s on your mind? What problems do you have that we could collaborate on and might benefit from each other? When I was in the government, I managed the international program among my responsibilities for a decade.

Tom Isaacs (38:38):

And I found that some of our biggest allies and colleagues were people doing the same thing that we were, only in another country, and we can learn from each other as a result of that. And so we come together and discuss issues. And as you might expect, based on this conversation, they tend to fall into two camps. Can we agree to work on things that will help all of us on the science and technology side? And there, what we’ve done is we’ve agreed to collaborate on underground research labs because many countries build laboratories underground first in order to study the characterization. And so that’s an ongoing program and very successful. We bring together scientists, technical people and program managers, and the other one is on what we call siting. The difficult part of how do we learn to work together to get best practices along some of the lines I’ve tried to share with you and share those among the various countries, so that we can all do our job better and have better prospects for success.

Kari Hulac (39:40):

Are there any countries there to watch, like any hints you can give us of anyone who’s kind of maybe moving forward well? Or a couple of those countries, you know, ones that we should keep an eye on? I know you’ve already mentioned Finland and Sweden, but anyone from that working group?

Tom Isaacs (40:00):

Okay. So they have had many of the same experiences we have in particularly in Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, they have very sophisticated, advanced, scientific and technical programs, but those are small densely populated countries with significant parts of them inaccessible for a repository. So they really don’t, the places where you could build a repository, usually have people, lots of people around them. So they have a big siting issue and we talked about that. The Australians don’t have commercial nuclear power, but they do have waste, intermediate level waste that they have to dispose of. And they’re looking at a technique, and this is something that should be of interest to Deep Isolation. They are looking at the boreholes, which is an alternative to a repository for disposing of waste. And so the Australians are beginning a pretty serious focused effort on looking for both the technique and the place to dispose of their low and immediate level waste. So I would say it’ll be very interesting to see how that program unfolds over the coming next years. The Japanese, Koreans, Taiwanese, for example, I think are still early in the siting part of this like we are at this point after all of this work and the Chinese just announced that they’re working on an underground research lab in the Gobi desert. So they’re beginning to get involved with this problem as well. And it’ll be interesting to see how that goes.

Kari Hulac (41:36):

Great. Well, it sounds like you have a really fascinating job. I can see why you’ve done it all these years. It must never get old. Thank you for joining us today.

Tom Isaacs (41:48):

It’s been a pleasure. I’ve enjoyed it. And if I were to leave one comment, I would say that the program needs continual infusion of new blood. And if there are people out there watching this who find this problem interesting, I think it’s a marvelous, frustrating, but marvelous job to bring together all elements of both society and you as an individual in order to be successful, I would encourage you to do that.

Nuclear Waste 101

Understand more about nuclear waste and its implications for you and your community.

FAQS

Deep Isolation answers frequently asked questions about our technology, our process, and safety.